Philosophical Rationalisation of a Geotechnical Narrative to Cost Overruns in Highway Projects- Juniper Publishers

Civil Engineering Research Journal- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Different methodological routes to the study of cost overruns are evident in the literature. A critical review reveals several gaps, particularly the lack of methodologically robust explanatory evidence to support the assertions that geotechnical risks significantly impact on cost overruns in highway projects. This study evaluates and select an adequate philosophical/methodological orientation relevant to provide a geotechnical narrative to the phenomena of cost overruns in highway projects. This paper thus sets out the underlying philosophical and logical reasoning that served as a guide on the conduct of a study, carried out to illuminate geotechnical trajectories to cost overruns in highway projects. Critical evaluation of the different philosophical stances evident in the literature was carried out, while factoring in the practicality and compatibility of the methods implicit in the various research strategies. The study adopted the philosophical stance of the critical realist, via the amalgamation of ontological positivism, with epistemological constructivism, in acknowledging the role that values and societal ideology play in the derivation of empirical knowledge on cost overruns. The case study approach was further justified as an appropriate research strategy necessary to provide a geotechnical narrative to cost overruns, in view of its: wholesomeness in investigating the study phenomena; ability to incorporate requisite multiple data sources and research techniques; and compatibility with adopted pragmatist philosophical critical realist viewpoint. The study espouses the need for objectivity, albeit a multi-perspective interpretative understanding of the human factors in organizational practice, that drive the more technical concerns about ground related risks, as a core requirement, necessary to provide a geotechnical narrative to cost overruns in highway projects.

Introduction

The term ‘Philosophy’, as used in general premise, refers to a ‘system of beliefs and assumption about the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality, and existences’ [1]. Philosophy in the domain of academic enquiry, provide the framework for how a research project is conducted, based on the researcher’s beliefs and assumptions, concerning what is valid as knowledge, and what process should be used to attain that knowledge [2,3]. For instance, Saunders et al., (2009:107) espouse:

“Our values can have an important impact on the research we decide to pursue and the way in which we pursue it. This may not lead to any form of discord, but it may mean that some observers accuse us of untoward bias”.

As such, the philosophy of research, stereotypes the way knowledge is derived and reported [4]. A vast array of terminologies has been used by different authors in the scholarly literature, to describe and explain the philosophy of research: Knowledge claims; Philosophical assumptions; Epistemologies and ontologies; Paradigms; Knowledge claims; World views [2 & 5-8]. Typically, within the context of social enquiry, Blake [9] described research paradigms, as the broader philosophical and theoretical traditions, which have served to provide a platform for addressing and understanding social issues. It was consequently asserted that, research paradigms provide a platform for the application of logic, in the linkage of people’s experiences and perceptions, within the wider context of the social world in which they inhabit. In this context, Blake [9] used the term ‘research paradigms’, to describe the theoretical underpinnings of enquiry, which is shaped by particular ways of viewing the social world, and the comprehension that stems from such views. Creswell & Clark [8], however, described the terms World view and Paradigm as being synonymous with the term research philosophy. Creswell & Clark [8], traced the terms back to their origin in the 1970’s, when Kuhn defined paradigm as a set of generalizations and beliefs common to a specialised discipline. Creswell & Clark [8], further, distinguished it from current usage, by describing research philosophy as the commonality in the shared beliefs and values of researchers, and how this affects the way research is conducted.

The Niger Delta was used as a study site to research the validity of geotechnical risk factors in explaining cost overruns, due to its peculiar wetland geology. The historical antecedents show the significant level of investment channelled to infrastructural development through several foiled bodies, which were specifically set up in recognition of the physical environmental constraints of the Niger Delta. The historical background reveals the prevalence of project delays and abandonment, as an ongoing legacy from the past to the present [10]. Empirical literature sourced, repeatedly highlights themes which revolved around funding shortfalls and technicalities associated the terrain. These findings led the researcher to hypothesize that the peculiar geologic setting coupled with the other underlying technical issues in practice, may be fundamental to the prevailing menace of delays and abandonment, leading to excessive cost overruns in the Niger Delta region. This created the impetus for probing further into what technical issues in the organisations responsible for procuring highway projects, have remained unresolved, from the past to present institutional arrangements. Against this backdrop, the aim of the study was to explain the propagation of cost overruns in highway projects using a geotechnical narrative predicated on the financial risk implications of the heterogeneous geology of the Niger Delta wetland.

It is therefore necessary that the philosophical stance taken, and assumptions made, about how and what will be learnt, in the process of conducting this research, is explicitly elucidated, as it informed the overall structure of the study on cost overruns, in reporting, as well as the manner in which data was collected, analysed and interpreted. This study sets out the detailed reflections and evaluations supporting the research methodology, which was the overall framework that served as a guide on all aspects of conducting a study on cost overruns, contextualised to provide a geotechnical trajectory. A distinction is however made between the terms Method and Methodology, which are often used interchangeably. Research method refers to “a more or less consistent and coherent way of thinking about and making [collecting] data, way of interpreting and analysing data, and way of judging the resulting theoretical outcome” [11]. Whereas research methodology is: “A strategy or plan of action that links methods to outcomes and governs our choice and use of methods [7]. Research methodology, as distinct from research methods, serve as a basic guide on all aspects of a study, from shaping the broader philosophical ideas that are brought to a study, down to the specifics of data collection and analysis. As Farrell (2011:23) underscores, “there is need for a detailed description of each step of the research process”, the components of the research methodology adopted in this study, are presented and explicitly defined exhaustively, in a hierarchical order. The study therefore provides the mind map of rationalisations in choosing a research methodology, projected as an interwoven synthesis of informed decisions made at the philosophical levels.

Elements of Research Philosophy

There are three major dimensions of research philosophy, about which core assumptions concerning the conduct of this research, were made: ontology, epistemology, axiology/ rhetoric [3,7,12]. These ontological, epistemological, axiological and rhetorical strands thus shaped the reasoning about how this research was conducted. They are thus defined apriori, as the basis on which the subsequent critical evaluation of the research philosophies is subsequently, necessary to select and adopt the most suitable orientation for the study, in providing a robust explanation, for the phenomenon of cost overruns experienced in highway projects.

Grey [12] explains ontology as an understanding of what reality is, i.e. the perception of what exists out there in the world (Hughes, 1990). It is thus a reflection of what the researcher views as being reality. At the ontological level of research philosophy, Saunders et al [3] mapped out two extremes of this scale; Objectivism and subjectivism, which frame the lenses with which researchers look at social phenomena (Grey, 2014). The objective school of thought isolates reality from social external influences, as opposed to the subjective, which emphasizes that reality is shaped by social forces. Hughes, (1990) therefore summarised the question of ontology, as hinging on the nature and significance of empirical inquiry, as to whether or not the world is factual. With this outlook, an ontological stance of either to adopt a singular (A world exists out there independent of our knowledge); or multiple (There are several ways of viewing the world), perception of reality, was taken. This decision was however made, in tandem with the intrinsic nature of the phenomenon being investigated: ‘Cost overruns in highway projects’, with a view to provide a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of it. Epistemology relates to the fundamental belief of a researcher concerning what constitutes knowledge. Epistemology is focused on how people identify knowledge and the standards that determine what can be said to be knowledge. The phrases: “What counts as fact?”, and “What is the character of our knowledge of the world?” have been used to describe epistemology. Epistemology of research thus hinges primarily on what is considered acceptable knowledge for a particular field or a particular study [3]. In this vain, the researcher’s perception of the nature of knowledge, and what is considered valid as constituting knowledge, dictated the approach to this study. Therefore, the legitimacy of knowledge as adopted in this study, was established at the epistemological level (Grey, 2014). This inherently manifested in terms of the level of bias introduced in this study i.e. whether the researcher maintained an objective distance from the facts or infused a subjective presence (researcher’s/participants’) into the research, as later elucidated.

The axiological strand of research philosophy revolves around what values go into conducting the research [3,7,13]. Axiology emphasizes the role of values on the conduct of a research and its effect on the credibility of research outcomes, as either being value laden or value free [3]. Researchers thus clearly recognize and acknowledge the impact of their values on study outcomes, if value laden. The axiology of the study thus defined how the values of the researcher were either been expressed in the study or conducted independent of the researcher’s values [12]. As subsequently elaborated, it informed the choices made by the researcher in collecting evidence, and the mode of reporting the study findings. The axiology of the research, therefore, was articulated explicitly in all facets of the research. Axiology as such, covers issues of rhetoric in terms of reporting findings, and how validity was ensured within the context of this study. Brinberg & McGrath [14] described rhetorical issues within the process of research as:

“The identification, selection, combination and use of elements and relations from the conceptual, methodological and substantive domains of a research study to ensure validity of research findings”.

Brinberg & McGrath [14] explained that rhetoric can be inferred, from the way a research is conceptualized and articulated. As it is dependent on the value or worth attached by the researcher, as to what is considered important in the subject domain, it determined which measures were logically taken to ensure generalisability, or a lack thereof, in this study. Typically claims to generalisability are not made in reporting findings, if the philosophical basis of the research assumes multiple realities and acknowledges subjectivity as to what constitutes knowledge [9]. In this vain, such study outcome may be considered ideographic, and analytic generalizations, nested within the confines of the specific setting, which adds to the knowledge domain may be made [15].

Evaluation of Potential Research Philosophies

Various authors [3,7,12] have categorised the philosophical positions adopted in the conduct of academic inquiry using varying terminology, often lacking explicit distinction. For instance, Creswell [7] outlined four distinct philosophical stances or theoretical perspectives in research, namely: Post-Positivism; Constructivism; Advocacy/participatory and Pragmatism. Whilst Grey [12] suggested the main philosophical positions include: Positivism; Interpretivism (Phenomenology, Symbolic Interactionism, Hermeneutics and Naturalistic Enquiry); Critical Enquiry; Feminism and Post-Modernism. Finally, both authors views are challenged by Saunders et al. [3] who discussed these philosophical views on the basis of four categories: Positivism; Realism; Interpretivism and Pragmatism, defining the relativity of epistemological and ontological stances, as an onion bulb.

Despite the multiplicity of different world views, positivism and Interpretivism, are consistently discussed in the literature, in relation to their contrasting ontological, epistemological and axiological stances, with a third world view, pragmatism, presented as a combination of both approaches in the more recent literature [3 & 8]. The debate in the literature, thus appears to be centred on the two extremes of positivism and interpretivism, as to what is reality, and what therefore should constitute knowledge. Positivism is repeatedly cited in the array of research philosophies because it is the foremost research approach, while Interpretivism and pragmatism have emerged as distinct classes of post-positivists philosophies. On this basis, therefore, the discussion of the literature, has been delineated and synthesized along the three broader divisions of the positivist, interpretivist and pragmatist perspectives.

Positivist/ Post-Positivist Philosophical Stance

Grey [12] reported that positivism was the dominant philosophical stance in the 1930’s, through to the 1960’s. This philosophical stance is based on the epistemological view that, the world exists externally and independent of the researcher, and that knowledge comes from observing the world around us [7 & 9]. It has been described as a theoretical stance analogous to working with observable facts, similar to the research tradition of the natural scientist or the physical sciences [3].

A term used by Blake [9] to describe positivism was ‘Empiricism’. Blake [9] described positivism as being based on the key assumption, that knowledge can only be produced by the objective usage of the human senses, and that this is the only sure and reliable basis on which research can be conducted. Saunders et al. [3] suggested that following the positivist tradition, the trained researcher should carry out a study scientifically, using and applying standard established procedures. Blake [9] described the positivist philosophical stance as “Having an undistorted contact with reality”. Additionally, Blake [9]further stated, this ultimately depicts value neutrality, necessary to yield an accurate representation of reality. In this way the researcher is seen as a ‘subject’ trying to study an ‘object’.

In the 1980’s the core principle of the positivist school of thought was broadened to reflect post-positivist views. This was based on an intellectual movement, which defied the absolute finality of the positivist tradition. This post-positivist stance challenged the traditional notion of absolute truth of knowledge, based on the reasoning that the positivist tradition was not applicable particularly when studying the behavior of humans. Saunders et al. [3] description of Realism appears synonymous with this post-positivist stance. The proponents of this school of thought, asserted that knowledge is conjectural, and that absolute truth can never be found, as it continuously changes in the light of new findings emanating from social reality.

The key attributes of the post-positivists philosophical stance are summarised by Creswell [7]:

1. That knowledge is imperfect and therefore refutable

2. That research is a process of continuous refinement of knowledge in the light of stronger evidence.

3. Rationality, data and evidence are the defining basis of what constitutes knowledge.

4. The reduction of ideas into discrete numeric measures of observation is pivotal.

5. The generation of generalizable causal statements is the central focus of inquiry

6. Objectivity is central to ensuring reliability and validity

Interpretivism

This is the major philosophical stance that has been identified in the literature as critical, and starkly opposing the positivist stance. Hammersley & Gomm [16] historically traced the evolution of interpretivism, as being the outcome of a long history of criticism of the hypo-deductive logic of the positivist tradition. This was based on the disparity between the laws of science and social reality, which therefore warranted different methodological approaches (Grey, 2014). The central argument proffered by the Interpretivist group was:

“Rich insights into this complex world are lost if such complexity is reduced entirely to a series of law-like generalisations” (Saunders et al., 2009:116).

On this premise, Crotty [5] emphasized the focus of the interpretivist on the qualitative uniqueness of individuals’ perspectives, as opposed to the positivist perspective, which seeks to establish consistencies in data as a basis of generating laws. Interpretivism therefore, relies on the subjective meaning given to reality by the participants in a study. As such reality is conceived as being multi-faceted, from the viewpoints of the human beings, regarded as the key social actors that define reality [17]. Creswell [7], described the researcher in this vain, as striving to derive meaning from the complexity of views, as opposed to narrowing down to a few categories of ideas.

The terms ‘social construction of reality’, ‘constructivism’ and ‘constructionism’ all refer to interpretivist philosophical stance, which emphasize that reality is socially constructed or interpreted [3,7,9]. Grey [12] used the phrase “Culturally derived and historically situated” to describe the Interpretivist philosophical perspective to research. As Creswell [7] reiterates, meaning and interpretation of subjects in such studies, are culturally and historically negotiated, through the process of interaction, and not simply imprinted on individuals.

It would however appear that, there is a diverse range of classifications in the literature on philosophical approaches, that by implication should be inclusive in the interpretivist world view. Some authors have categorised all anti-positivist philosophical stances as being Interpretivist [3]. Yet some have isolated and listed interpretivism as one of the numerous world views, alongside others such as feminism, critical theory and realism [9 & 12].Creswell [7] however, grouped philosophical approaches that advocate for specific social and marginalised causes under as participatory/emancipatory world views, as distinct from those of the Interpretivist. This was rationalised, in view of the shortcomings of the interpretative approach, in addressing specific social issues about marginalised groups of people in society.

In the researcher’s view however, all the other philosophical perspectives which rely on the need to emphasize the values of the researcher and the participants can be grouped under the broader perspective of interpretivism. This, in the opinion of the researcher, is because the key distinctions noted amongst these philosophical groups, are the differences in the levels of involvement of the researcher and the participants, as well as the specifics of the subject matter being investigated. Along similar line of logic, Blake [9] analysed the differing stances adopted by researchers within the context of socially constructed knowledge. The author described the researcher in this scenario as being an ‘insider’ and a ‘learner’, while noting the distinction in terms of the researcher’s stance as to ‘being for’, ‘being with’ and ‘partnering with or conscientizing with’ the participants. Creswell [7], also explained the researcher’s stance as being either ‘collaborative’ or ‘understanding’ and geared towards change or theory generation.

Pragmatism/Critical Realism

Creswell & Clark [7] referred to pragmatism as “the third major philosophical movement”. Pragmatism as the name implies, is a philosophical position which is practical in nature. It thus relegates the philosophical debate of singular or multiple realities, in terms of epistemology and ontological arguments, to the background. John Dewey is considered the pioneer author of this philosophical movement, which criticised traditional epistemologies on the basis of the “too stark a distinction between thought, the domain of knowledge, and the world of fact to which thought purportedly referred” [18]. Dewey thus queried “Is Logic a Dualistic Science?” and coined the phrases “theory of inquiry” or “experimental logic” as more amenable to the practicalities of carrying out research [19]. To the pragmatist therefore issues emanating from the dialectical epistemological, ontological debates should take a backseat to the more cogent issue of the research problem and how best to provide an understanding of it. [3,7]. Creswell & Clark [7] stressed that the focus of pragmatism is on the research questions and the consequences of the research, which should ideally be of primary importance. Whereas, Grey [12], stated that, the practicality of the need to provide answers to different research questions, may warrant different philosophical approaches. This is on the grounds that a philosophical approach adopted for one research question, may be inappropriate if applied to another. The use of pragmatism as a world view therefore accommodates the use of both subjective and objective knowledge.

Tashakari & Teddlie [20], noted thirteen different authors who clearly stated the need for a philosophical stance that was all encompassing, without the need to engage in philosophical arguments. This was rationalised on the premise that pragmatism has a trajectory that is rooted in practice and thus devoid of the divergence implicit in other philosophical perspectives. It was asserted that, most modern-day realism and empiricism have adopted variants of the pragmatist philosophy, by relegating philosophical arguments to the background, rather focusing on the specifics of the problem being investigated and the relevant methods to tackle them.

There are however authors who have expressed the need for caution in adopting pragmatism as an all-embracing world view, without explicitly defining the underlying ontological and epistemological stance of the researcher, describing it as more akin to intellectual laziness. Typically, Holden & Lynch [4] stated that. “if a researcher perceives ontology and epistemology to be irrelevant, then how can they ensure that their methods are really appropriate to the problem in hand? Conceivably the problem could be better investigated with a method from an alternative philosophical stance”. Moore [11], in the wake of the rising acceptance of pragmatism inspired by John Dewey’s works, reviewed a compilation of studies by critics who challenged the philosophical position of pragmatism. The major issues cited were looseness in the use of the term ‘practical purpose’; the implied subjectivity/relativity of the position; and the lack of a unifying prescriptive principle [11]. The theoretical application of the pragmatic world view is thus still subject to debate in the literature. In more recent works, Greene & Caracelli [21] argued that the use of multiple world views gives rise to irreconcilable differences in research, and rather emphasized the need for a differentiation of world views with respect to specific parts of a study. Similarly, Creswell & Clark [8] advocated that the multiple philosophical stances used within a study needs to be explicitly defined within the research.

Critical realism has been argued to be a variant of the pragmatist philosophy, albeit one with a clearly defined ontological and epistemological positioning: that social reality exists not only in the mind, but in the objective world and can thus also be objectively studied [22]. Typically, Lipscomb [23] expounds: “Pragmatism has been advanced as one means by which the Gordian knot of theoretical dispute can be cut and critical realists have, in recent years, also asserted same”. The critical realist philosophical positioning also termed ‘transcendental realism’ by Huberman & Miles [22], albeit controversial, is however backed by a rigorously argued intellectual justification by its proponents. The justification of the pragmatic-like philosophical positioning of the critical realist, as reinforced by its proponents: Huberman & Miles [22]; Frazer & Lacey [24]; and Campbell [25], is thus rationalised beyond the pragmatist mantra, ‘practicality of the research’, which has evoked major criticism from both the positivist and constructivist traditions.

Critical realism evolved from the post-positivism movement of realism, which views ‘reality’ as “whatever it is in the universe that causes the phenomena we perceive with our senses” [27]. It was further stated that there is no objective or certain knowledge of the world, admitting to the possibility of alternative valid accounts of any phenomenon. Saunders et al. [3] described realism as a predominantly objective positivist stance, but one which is conditioned by social reality. The authors distinguished between direct and critical realism on the basis of how the human senses perceives reality. From the critical realist’s position, human knowledge of reality is a result of social conditioning and cannot be understood independently of the social actors involved in the knowledge derivation process [26]. Other authors such as Groff [27] concur with this description of critical realism but emphasise more on its empirically inclined post-positivist nature typical of all forms of realism, espousing: critical realism offers a “point of entry into epistemology and metaphysics for practicing social scientists”. Whilst Carter (2000:1) is of the view that “critical realism attempts to reconcile the threatened divorce between social theory and empirical research”. Critical realism, which is thus more common in the social sciences, entails the concomitant retention of both an empiricist ontological view and a constructivist epistemological relativism [25]. It recognises that diverse valid perceptions and understanding of a research phenomenon is tenable.

Adopted Philosophical Stance

The choice of an appropriate research paradigm is critical to producing meaningful outcomes. Gajendran [28] alluded to several considerations in choosing a philosophical/methodological stance, stating that:

1. The subtlety of the paradigm variations demands deep engagement with the literature to perceive the differences. 2. Researchers need to carefully evaluate and respond to critiques of the chosen worldview and why it will deliver meaningful outcomes. 3. The need to accommodate the practicality of the research design, as aligning the conceptual research design to the operational research design is a frequent challenge faced by researchers.

Taking into consideration, the guidance offered by Gajendran [28], and having analysed the different philosophical stances evident in the literature, the researcher made an informed choice in the selection of a research philosophy, in tune with what is considered most appropriate to achieve its objectives, while factoring in the practicality of the methods implicit in the choice. The researcher towed the preceding line of logic of the critical realist, as the appropriate philosophical lenses through which the aim of this research and its objectives was achieved. This dictated that the altercation between the empiricist and subjective philosophies be squashed. This choice was further informed by the necessity of incorporating multiple perspectives from project participants in highway organisations, inherently manifest in their accounts, which had to be sourced and interpreted by the researcher to understand the complexity of the phenomena of cost growth leading to cost overrun in highway projects. As Saunders, et al. [3] asserts: “Focusing on practical applied research, integrating different perspectives to help interpret the data”, thus making the adoption of a purely positivist approach to cost overrun research impractical.

Axiologically, the values of the researcher were therefore manifest in the research as the researcher sought to interpret and derive meaning from the varying participant’s descriptive explanations of their organisations’ approach to the management of ground related risk. The potential for subjectivity as the respondents describes the design and costing approaches in the highway agencies, further underscores the role that values play in the knowledge derivation process of this research. This defining characteristic of the study further made knowledge derivation on the pure empiricist basis of positivist philosophy, inappropriate. Subjectivity that may be attached to the interpretation of results by the researcher on this basis is therefore acknowledged

Grey [12] summarised the applicability of positivist and interpretivist approaches, as being in line with truth seeking and perspective seeking methods, respectively. The latter is the fundamental ideology of the study, and not the basic underlying axiom of the former: ‘The impersonal development of theory for generalizations. Claims to generalizability of findings from this study are thus not made on this premise. Unlike positivism, in which scientific knowledge is statistically generalised to a population, the critical realist perspective adopted in this study strives for theoretical generalisability of the socially derived knowledge, that is how the analytical outcomes of this empirical study can fit in or ‘nestle’ with or within existing theories [14]. The position of the critical realist stance of this study is thus also distinct from pure constructivism, which asserts that reality is socially constructed, and thus as individualistic perceptions, cannot be generalised. On this basis therefore, in the adoption a critical realist philosophical stance, to provide a multi-methodologically robust explanation for cost overruns experienced in highway projects executed in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, the researcher pre-supposed and acknowledged the:

1. Differences of opinions on the ongoing geotechnical practice in highway organisations and their contractual affiliates.

2. Role that the geology of project location, particularly in wetland terrain, has to play.

3. Contextual geo-political institutional dynamics of highway development in the Niger Delta.

4. Underlying technological constraints in the developing world.

5. Value laden role of the researcher in interpreting and reporting findings, which underscores the need for triangulation of findings from various sources.

Evaluation of Potential Research Strategies

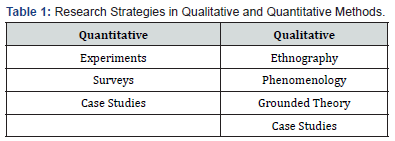

Research strategy can be defined as the means of designing an enquiry, in order to turn research questions into projects. This essentially frames the overall study approach [29]. This crucial element of scholarly enquiry, Robson [29] further stressed, should be addressed with adequate consideration given to the plethora of issues and possibilities from the wide range of available research strategies. As listed in Table 1, these strategies are typically associated with qualitative or quantitative research, with the notable exception of case studies, whose applicability traverses both types of research method.

Strategies utilised in quantitative methods, adopt a positivist philosophical perspective of objectivity. As such quantitative researches are mostly associated with experimental type studies: true experiments and less rigorous quasi-experiments, and surveys which require the generation of theory to enable generalisations [8].

Qualitative research strategies, characterised by an interpretative stance, are more closely associated with attitudinal studies of individuals or in organisational research, often requiring the researcher to be closely linked to the study site and the participants [30]. They are therefore humanistic and interactive with the researcher being highly participatory [7]. Qualitative research is predominantly associated with strategies such as ethnography, grounded theory, phenomenological research and even case studies, which have been shown to be adaptable to both quantitative and qualitative studies [15].

The researcher in this study, in view of this variety of options makes a conscientious choice as to which strategy can best serve to achieve the aim and specific objectives of the study. The basis of this decision however stems from the applicability of each type, in relation to the research questions or study objectives [3]. It was thus stated that:

The general principle is that the research strategy or strategies, and the methods or techniques employed, must be appropriate for the questions you want to answer” [29].

This is because for any choice made there are basic underlying set of assumptions, advantages and disadvantages which must be

The evaluation begins with the purely quantitative strategies before appraising the qualitative approaches. Ethnography and phenomenology listed amongst the purely qualitative research strategies are however excluded from the detailed evaluation, based on their abstract nature and emphasis on cultures and peoples’ lived experiences, which is beyond the scope of this research and due to their philosophical incompatibility with the empirical nature of the critical realist stance adopted in this study. The evaluation of the purely qualitative strategies herein is thus limited to grounded theory, due to its fundamental applicability to all qualitative research. Case study research which straddles both methods of research concludes the evaluation.

Experiments

The deployment of an experimental strategy is often associated with the empirical approach of conducting research [29]. Experiments have been defined as an empirical investigation which is conducted under simulated conditions, as a means of eliciting defining properties or relationships existing between identified variables [17]. Descombe [17] identifies three fundamental criteria for the use of experiments, these include:

1. The underlying assumption of causality in the variables. 2. The deployment of controls as a mechanism for exclusion. 3. Empirical observation of a phenomena and detailed measurement.

It is therefore clear that the basic rationale for undertaking experiments is to establish cause-effect relationships amongst variables, which will form a platform for the formulation of generalizable theories. The repeatability, precision and credibility which are requisite of experiments, however, cannot be feasible in a research of this nature. This is because of the impracticality of being able to manipulate the variables under study: Ground conditions in the Niger Delta region and the geotechnical practices in highway agencies, to suit an experiment type research. Within the context of this research, experiments therefore, do not provide an adequate strategy for investigating the phenomena of cost overruns in highway projects.

Also, the highly objective nature of experiments does not make it amenable to carrying out this research, which recognises the subjective influence of human beings as the key medium through which information would be gathered. The artificial and intensively structured nature of experiments therefore cannot serve to achieve the study objective of understanding the practices of highway agencies in terms of the level of adherence to geotechnical best practices. This study is not artificially contrived, but is carried out in a real-life scenario, which is set in the social context of the highway organisations.

Surveys

The word survey can assume different meanings depending on the context of its usage. Descombe [17] highlighted a definition of survey, from the geographical perspective of surveyors, as the need to obtain data, which can be applied to mapping out the social world. Surveys in a research context however have been generally used to refer to the collection of standardised information from a population or sample most commonly with the aid of questionnaires or structured interviews [29]. Carrying out surveys is a principal strategy that provides quantitative measures of trends, attitudes or opinions based on samples derived from a wider population [7]. Surveys do not incorporate any specific methods of data collection but rather can be carried out using different tools [17]. Types of surveys include postal and internet questionnaire surveys; face-to-face surveys (interviews), observations and documents. Each of these types of surveys have basic advantages and disadvantages, and it therefore falls to the researcher to weigh the options in the light of the kind of information sought [17, 29].

Surveys can be conducted as cross-sectional or longitudinal studies. Surveys often conducted on the spot within a specified time frame with the general intent of bringing things up to date are cross-sectional in nature [15]. They thus provide a structured and instantaneous snapshot of a specific event at a specific point in time. This is as opposed to longitudinal studies where research spans a longer time span. The choice of conducting longitudinal survey research is usually with the intent of tracing the development of changes in phenomena over time, typically required for time series analysis [15].

The representativeness and size of samples in a survey research are critical issues that define the level of generalizability of research findings [7]. Descombe [17] thus emphasized that one key characteristics of a survey research is “Wide and inclusive coverage”. This inherent advantage of the survey research strategy makes it a potential strategy for most research in terms of its wider coverage. However, although the comprehensiveness of a survey may cover a wider range of participants due to larger sample size, the depth of information obtainable from surveys is often limited [15].

The data to be potentially gained using survey is allowed to ‘speak for itself’ leaving out the finer details [17]. Implications of using survey as the strategy for this study, would thus be that context would be lost, a major shortcoming spotted by the researcher, as a significant gap in the bulk of the previous research on cost overruns. Characteristic features in organisations, such as how the hierarchy of authority impacts on design and estimating practice, facts which can only be relayed via the richness of data from descriptive narratives, will be missed out. As such holistic background information on the complex inter-related design and costing processes, functions and job designations within the organisational structure of the highway agencies, which can affect the understanding of the study phenomena, may not be elicited from surveys which produce structured responses.

In the context of this study, the empirical nature of survey research, which lends itself more to objectivism on an axiological scale, leaves out the interpretative element which is the driving philosophical root of this enquiry. This lack of ‘texture’ and ‘feel’ by virtue of the highly structured and objective format of survey questions, will thus prove to be a major shortcoming for this study. A more in-depth approach is therefore deemed appropriate, to achieve this study’s objective, of assessing the geotechnical adherence evident in highway projects executed in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria.

Grounded Theory

The origins of grounded theory can be traced back to the work of Glaser & Strauss [32]. Their development of the grounded theory approach was in direct opposition of the logico-deductive methods of science which entailed the testing of preconceived theories based on empirical field work [32]. Their criticism of the scientific method was on the premise that such theories often do not fit in with real life scenarios and therefore remain ungrounded. The authors thus advocated the development of theories that were firmly rooted in the practical reality of a phenomena, particularly in the study of people and their interactions. Grounded theory as a research strategy is closely linked with the symbolic interactionism philosophical reasoning [33]. On this basis grounded theory advocates for a continuous adjustment in the perception of reality on the basis of new meanings derived from human interaction. According to the original version of grounded theory advanced by Glaser & Strauss [32], the researcher is expected to approach the study with an open mind, without relying on any preconceived notions. The accumulated bulk of existing theories are therefore not relevant at the onset of the research. This has however been a point of considerable debate in the literature, on the grounds of the practicality of any researcher being able to achieve this state of ‘blankness’ [17].

Strong views were expressed by other researchers in opposition to the notion of blankness, as being philosophically impossible because to a large extent, it is these preconceived notions that would have led the researcher to conduct the research [17]. This initial extremist position of ‘blankness’ was thus later modified by Strauss & Corbin [32] who acknowledged that prior experiences and theories should have a role. According to Strauss & Corbin [32], this was due to the acknowledged fact that any research must have a ‘beginning focus’ from which to start. However, it was stressed that such theories should be viewed as ‘provisional’ in relation to the study being conducted, pending the outcome of the research. Thus, it was stated that:

“The initial questions and areas of observation are based on concepts derived from literature and experience. Since these concepts do not have proven theoretical significance to the research, they must be considered provisional” [32].

Although the need for empirical fieldwork is emphasized in the deployment of grounded theory, it is necessary that theories be allowed to emanate from the field and not to be generated at a high level of abstraction and then tagged on to present situations (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). The emphasis is thus that theory should be systematically generated, and gradually developed based on emerging trends which can then be generalised. The collection of data should therefore be systematic and not just amassed with expectation that the data would speak for itself [17]. This systematic nature of data collection is carried out at the first instance on a broader platform. Subsequent data collection become increasingly directional and focused, in line with the flow of conceptual categories that is seen to be emerging from the data [32]. The selection of instances that would be included in a grounded theory research is thus dictated by the patterns of concepts that can lead to theory development.

On the basis of these fundamental requirements outlined above, the potential applicability of grounded theory to the purely qualitative element of in-depth interviews used in eliciting information describing current practices is still limited by the inherently theory driven nature of grounded theorising. Another challenge posed through the adoption of a grounded theorist approach to qualitative data analysis, is that grounded theorists carry out continuous theoretical sampling based emerging theoretical categories. This is carried out up to the point of theoretical saturation, a stage in the research at which the addition of further instances does not add any new perspective to the research [33]. This requirement to systematically reduce the scope and number of instances studied in grounded theory researches, in effect practically constrains its applicability in the context of this study. This is because the analytic boundaries of the qualitative analysis in the study directly impact on the availability of cases to utilise as a basis of achieving theoretical saturation. Another shortcoming identified in the potential adoption of grounded theory for use in this research is its limitation to purely qualitative researches. The need to evaluate numerical as well as textual data from the field work, thus refutes the fundamental purely qualitative premise of grounded theorising.

Case Study

Robson [29] contrasts survey methods with case studies in terms of the level of information obtained from participants. Surveys typically require a limited amount of information from respondents due to their highly structured format, while case studies depend on collecting extensive information from identified informants. In research where depth of information rather than breath is emphasised, case studies thus offer a distinct advantage. This distinguishing quality of depth afforded by the use of case study affords a central focus on the instance being investigated, i.e. “To illuminate the general by looking at the particular” [17]. Whereby the ‘case’ is the situation, individual, group, organisation or the prevailing phenomena that has warranted the study.

The underlying logic of ‘replication’ typical of empirical enquiry in case studies, concomitantly means that the case may be extended to cover multiple instances. The rationale behind using one case or a few selected cases arises out of the need to focus attention on typical instances as opposed to mass studies, is to uncover useful insights which may simply have been glossed over. The generalisability of theories generated from case study research are thus directly correlated with the number of cases studied. Multiple case studies are thus deemed to have higher levels of generalizability than single case studies, as they enable cross-case comparisons. Cases selected on this premise must therefore be comparable.

Yin [34] also stipulated three fundamental conditions that must be used in deciding the applicability of case study as a research strategy: “Nature of research questions (‘How’ and ‘Why’); The extent of control the researcher has over actual behavioural events; The degree of focus on contemporary issues”. Typically, the case study approach is logically deemed appropriate to provide answers to ‘How are estimates for road projects in the Niger Delta region prepared at the pre-contract phases of highway projects?’ With respect to the degree of control the researcher has over actual behavioural events, the researcher has no influence directly or remotely on the costing and design practices prevailing in highway agencies in the Niger Delta. The information sought are practices that are ongoing, and thus cannot be manipulated by an external observer (the researcher) outside the case. The ‘degree of focus in a research: on contemporary or historical events’, posited as the third criterion by Yin [31] has however been argued by other authors, who noted that although case study research is predominantly associated with contemporary phenomenon, they can also be historical [35]. Irrespective of this argument, this central issue of cost overruns in highway projects is a very topical one, which has attracted, and is still receiving attention from scholars, construction professionals, stakeholders as well as continuous local and international media exposure. As Yin [15] underscores, the most outstanding characteristic of a ‘case’ or ‘cases’ in a case study research must be its significance, which may be of public interest; with theoretical, practical or technically distinctive underlying issues,

Adopted Research Strategy

Experiments and surveys are deemed inapplicable to this research by virtue of their purely positivist philosophical underpinning, which is devoid of context, and restrictive of the depth of evidence that can be sourced. As such the restrictive, artificialized and highly structured nature of positivists methods, with their implied logico-deductive approach negates the wholesomeness which the researcher considers pivotal to investigating and understanding the interrelated processes and functions in cost estimating, designs and contracting for highway projects. Furthermore, the distinction between the study phenomena and its context is highly blurred and thus cannot be divorced to suit the structured format of experiments and surveys. From a philosophical perspective, the interpretivist philosophical root of grounded theory aligns more closely to the philosophical underpinning of this research, than the positivist underpinning of experiments and surveys evaluated. However, the ‘theory building from qualitative data’ objective of grounded theorising, which Corbin and Strauss (1990) explained as ‘seeking to develop a wellintegrated set of concepts from the data, that provide a thorough theoretical explanation of phenomena under study’, is a limitation in this research. This is because, although the study seeks ‘to provide explanations for cost overruns’, the relevant application of the existing body of theoretical propositions in cost estimating, highway designs and geotechnical engineering to the data is implied.

The need for a more encompassing research strategy, that is compatible with the critical realist philosophical stance adopted in this study, therefore made the adoption of experiments, surveys or grounded theory, as an overall research strategy for this study, inappropriate. Based on the overall assessment of the applicability of all the research strategies, the case study approach was deemed the most philosophically, technically and practically compatible with achieving the objectives of this study, based on its:

a. Appropriateness/Wholesomeness in investigating the Study Phenomena

In the context of this study, the depth of information needed to achieve the objective of the study, lends itself to using a case study research strategy, as depth rather than breadth of information is emphasised. Yin [15] provided a technical definition of a case study as: “An empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context”. Yin [15] compared this distinguishing feature of a case study to those of experiments, where there is a clear-cut purpose of stripping off the context. As such although surveys to a certain extent can investigate a phenomenon and its context, its ability to investigate the context is extremely limited. Adopting a case study approach was thus considered the most logical choice for the purpose of providing a robust and in-depth explanation of cost overruns experienced in highway projects, executed in the Niger Delta region, against the backdrop of its peculiar geologic configuration. It is thus considered as being the most suitable holistic approach, necessary to demonstrate the far-reaching impact of geotechnical pathogens on the current state of highway project delivery in the study area.

b. Capacity to Incorporate Multiple Data Sources and Research Techniques

A discernible characteristic of case study strategy considered requisite in this study, apart from its ability to explore in-depth a single phenomenon while retaining its natural setting, is its ability to incorporate a variety of methods [34]. This distinguishing quality of case study research, to accommodate different qualitative and quantitative data and techniques, yielded the richness of evidence which the researcher considered pivotal to achieve the study aim. This salient feature of a case study research enabled the researcher to source data from multiple sources. This study deployed a systematic quantitative analysis of project cost data, as well as geotechnical data, prior to a detailed qualitative evaluation of textual data. Adopting the case study strategy thus provided a platform for incorporating these diverse data types.

c. Compatibility with the Adopted Critical Realist Philosophy of this Study

Based on the study’s critical realist underpinning philosophical positioning, the epistemological, ontological and axiological implications of this stance as earlier clarified, is more of relativity in positioning, between the extremities on the continuum of philosophical spectrums. On this basis therefore, purely positivism based (Experiments and Surveys) or wholly interpretivism based (Grounded theory) research strategies are rendered incompatible with the philosophical stance of this study. Further establishing the compatibility of the case study research strategy, is the fact that although it acknowledges the social construction of knowledge, it is guided by theoretical propositions, which retains the element of empiricism necessary from the critical realist lenses, to infer causality. The critical realist philosophical viewpoint, which is the guiding principle shaping the design of this research, can therefore only be justifiably operationalised in this study by the adoption of the case study research strategy.

A Geotechnical Narrative: Nature of the Case Study Research Questions

Yin [15], relates the nature of the research questions guiding a case study in terms of ‘how’, ‘why’, ‘when’, ‘what’ and ‘where’ to the type of research: exploratory; explanatory; or descriptive, being conducted. ‘What’ questions are predominantly exploratory which seeks to explore a phenomenon in more detail, ‘How’ and ‘why’ questions are mostly linked to explanatory studies while ‘when’ and ‘where’ research questions are more descriptive. This study was thus concerned with not only the what’s, but the how’s and why. A geotechnical narrative therefore requires an explanatory/descriptive perspective, to understand the specific nature (What) and extent to which (How much) geotechnical risk impacts on cost; as well as (when) and (where) the susceptibility for cost overruns due to ground related risk occurs; necessary to infer causal links between geotechnical factors and cost overruns.

Although it may be argued that the phenomenon of cost overruns in highway projects is not a novel concept that should warrant an exploration, this study explored the peculiar heterogeneous and predominantly wetland geologic setting of the Niger Delta as a test bed for understanding financial risks due to the ground. In tandem, it sought to provide an in-depth descriptive account of how lack of geotechnical best practices can further exacerbate the propensity of highway projects to run over budget. The exploratory phase of the study was thus geared towards the identification of geotechnical pathogens, through a technical literature review. The descriptive element of the study therefore sought to provide a snapshot of the design and costing practices currently being deployed by the highway agencies in the study area. According to Hendrick et al. [36] a descriptive study provides a picture of a situation as it occurs. As Grey [12] opines, descriptive research is relevant to give a snapshot of a situation, person, or event or to show relationship within a defined structure. The explanatory perspective of the study centred on the study’s aim of explaining the high level of cost overruns incurred in highway projects, and the prevalence of lengthy delays and abandonments in the Niger Delta region. Explanatory studies seek to provide factors or reasons accounting for a descriptive study [22,37]. As Huberman & Miles [22] asserts: There is need, not only for an explanatory structure, but also for a careful descriptive account of each configuration. Such explanations were sought from the local literature, the scholarly literature, and the literature on geotechnical best practice.

On this basis therefore a geotechnical narrative to cost overruns should be designed as a normative study, to evaluate what happens in practice, in relation to what ideally ought to be in theory, following the requirements of geotechnical best practice [38-41]. The research thus centered on investigating how applicable current theory emerging from academe, the intricacies of the wetland geology of the Niger Delta, and the technical requirements of geotechnical best practice, in explaining cost overruns in highway projects.

Conclusion

This study has articulated all the elements of the research methodology of a case study of geotechnical risks leading cost overruns, from the higher order philosophical underpinnings of the study, down to the more practical issues of selecting an adequate research strategy. Incisive arguments and justification of the choices made at each level of the hierarchy of the research elements has also been provided. The critical realist philosophy operationalised via the case study research strategy has been justified as an appropriate lens necessary to provide a geotechnical narrative to cost overruns, within the purview of a range of presuppositions. This was underpinned by the need to concomitantly analyse the peculiarities of the wetland conditions in the Niger Delta (a physical entity), the techno-economic dynamics of the developing world (A techno-socially constructed entity) coupled with the geotechnical drivers (Technical) embedded within organisational practices (Socially driven). The adoption a critical realist philosophical stance, was thus deemed necessary to provide a multi-methodologically robust geotechnical explanation for cost overruns experienced in highway projects executed in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Critical realism in tandem, with the philosophically hybrid orientation of the case study approach, thus has the potential to provide holistic answers to the nature of research questions necessary to provide a geotechnical narrative t cost overruns in highway projects executed in the Niger Delta region.

For more about Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/journals.php

For more Civil Engineering articles, please click on: Civil Engineering Research Journal

https://juniperpublishers.com/cerj/CERJ.MS.ID.555786.php

Comments

Post a Comment