Safety as Project Success Factor in a Civil Project: A Case Study- Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers- Journal of Civil Engineering

Abstract

The civil industry is clearly lagging behind in

safety performance compared to the chemical and process industry and

more specifically to the oil & gas industry. Already for years the

oil and gas industry is advocating a zero incident policy and they are

making visible progress towards an incident free working environment for

own staff as well as contractor staff. In many situations a project

will be considered failed in that industry if an incident with lost time

occurred. This is in sharp contrast with the civil industry where even

last month you could hear people say that zero incidents is impossible

to attain. With the present case study it will be shown that with simple

measures and a real attention to staff and their well-being this goal

zero is attainable and actually creating the boundary conditions for

overall project success.

Keywords: Safety; Civil construction; Infrastructure; Project management; Contracting; BowtieHighlights

a. Civil construction projects can have a good safety record like the process industry

b. A goal of zero incidents is attainable in the civil industry

c. Real attention to people on a project and the working conditions makes a difference

d. The safety approach has to be fit for purpose, adapted to the specific industry

Introduction

For people who work or have worked in the chemical

and process industry personal safety as well as process safety has

become a second nature. This has taken many years and a lot of

attention, but safety statistics of this industry clearly show that

major steps forward have been made although not all companies have an

impeccable record yet. However, over the last 20 to 30 years the

improvements have been impressive. Incidents unfortunately still do

happen, but are getting scarcer luckily, and these incidents do have a

huge impact not only on the life and the personal circumstances of the

victim(s) but also on the personal norms, values and beliefs of both

managers and staff. Once you have lived through an incident with severe

consequences such as permanent disability (or worse fatalities) of your

staff, people always pledge “once, but never again”.

Unfortunately for some of them that insight might

have come too late. People who are educated and trained in this way

almost always change their behaviours with respect to safety and apply

their learning in every situation, being at home, on a journey or when

taking up work in a different industry. They do act as safety champions

and are trying to make a difference in that new industry. The firm

belief in the process industry is that when you are able to control

safety, you are also controlling quality, time, budget and the like.

After all with a clear focus on safety, you start thinking in risks,

their consequences and the mitigating actions. And these apply equally

well to the other areas that you are supposed to control or monitor.

When people complain that all these safety measures are driving the

costs up, the reply should simply be that the measures are far cheaper

than dealing with the consequences of an incident, an accident or a

fatality. On top of that, most of the measures are actually already

legal requirements in most countries. Complying with the laws on labour

legislation will be the first step towards an improved safety

performance, but more still has to be done.

In the present study a project executed in the civil

construction industry has been evaluated in more detail. The civil

industry has traditionally been lagging behind in their adherence to

safety legislation and compliance with the safety rules. There is still a

bit of a macho culture, doing things based on years of experience where

taking precautions, the lowest level of safety awareness, is already

seen as a weakness. Within the project under study it has been shown

that the performance on the subject of safety can drastically be

improved and consequentially the performance of the project overall is

at the same time much better than other projects in the civil industry.

The study will not only be focussing on safety but also on the overall

management of the project, since the authors strongly believe that the

two are closely interconnected.

The present case study is based on the experience of

the project team, gathered via interviews and observations, and has been

evaluated based on interviews with staff, interviews with management of

all the participating companies and by discussions with experts in the

field of project management, safety and contract management. In the

second paragraph a brief overview ofthe development of the safety

approach in the process industry and the civil industry will be

highlighted. In the third paragraph the approach followed in managing

this particular project will be detailed after which in the fourth

paragraph the specific approach for improved safety is explained. In the

fifth paragraph the experiences of the management teams of the

participating companies will be evaluated via interviews. The study and

the learning will be concluded in the final paragraph.

Literature

The literature on safety is abundant. It is not the

intent to summarise it all here, but a few of the important elements

used in the present project will be highlighted. As will be shown later,

staff coming from the process industry has triggered the present

approach. Starting from the present thinking in the process industry,

the switch will be made to the civil industry. In order to set the scene

a quick scan has been done on the reported safety statistics in the two

industries that we have been talking about up to now. The oil and gas

industry versus the building sector. The international organisation of

Oil and Gas Producers reports the safety statistics for the whole of the

sector annually [1].

The lost time injury frequency, the number of

incidents with loss of labour of more than 24 hours per million hours

worked, is for the whole of the sector 0.45. This is in sharp contrast

to the building industry. The Dutch Investigation Council for Safety

reports a LTIF of 33 over the years 2001 to 2011 [2].

Almost two orders of magnitude difference. Admittedly the number for

the oil and gas industry is not equal to zero, so accidents do still

happen, but it is a marked difference to on the one hand the statistics

for that same industry 10 or 20 years ago and on the other hand the

present day statistics of the building sector. OGP is counting in their

statistics all workers in the industry, both company staff as well as

contractor staff. The Safety Council has looked at all workers on the

payroll. These data are therefore comparable.

More statistics can be gathered once a deep dive is

taken into the annual reports of the various construction companies, the

owner companies and suppliers. Unfortunately in that case the data are

certainly not comparable. Most of the construction companies report the

statistics for their own staff in the annual reports and leave the

statistics for their contracted staff conveniently out. So looking at

all those statistics will give a wrong and clearly too optimistic

impression, but for completeness sake the LTIF figures are summarised in

Table 1 for a selection of companies. The companies are listed in alphabetical order.

These statistics do trigger for the experienced

safety supervisors another concern. Once there are more than 30 lost

time incidents things are bound to get worse. The theory of Heinrich, by

now maybe somewhat dated and not always straightforwardly applicable,

tells us that a more serious incident is going to happen. This is not a

fatalistic view of the world, but the statistics develop in this

direction according to the theory. The original theory is published by

Heinrich [3]

in 1931 in an article title "Industrial Accident Prevention: A

Scientific Approach". Heinrich showed in this article that every

accident with severe injuries (or worse) is preceded by 29 incidents

with a light injury and 300 incidents without injury. This has been

graphically represented in Heinrich's triangle.

In 1969 Bird [4]

has adapted the ratios to 600:30:10:1 representing incidents without

injury, incidents with damage, incidents with light injuries and

incidents with heavy injuries. At the moment the process industry is

using the ratio 3000:300:30:1 in which also the severity has been

adjusted. The top of the triangle nowadays represents the number of

fatalities.

Although over 80 years old, the theory of Heinrich is

still referred to. Within safety science it is almost seen as a law of

nature, although there is also some criticism. Since publishing the

theory the number of small incidents has clearly dropped, but the larger

or heavy incidents with serious injuries are not declining with the

same pace. So preventing the smaller incidents is not the approach to

also reduce the larger incidents. The opposite is truer: when a serious

incident has taken place, investigation afterwards shows that a number

of smaller incidents following a similar pattern have preceded the large

incident but with less or without any consequential damage. In these

cases some of the barriers between cause and effect have actually

worked.

Supported or not the triangle has focussed the

attention on the human behaviour, in organising the processes as well as

in the execution of work. Since mistakes can always be made, the utmost

has to be done to design the processes as far as possible as

“fail-safe”. So only focussing on labour safety is not enough, but

certainly a first step to improving overall safety statistics. At the

end the whole organisation has to be studied in order to operate safely,

meaning incident free. A mature organisation will have to be managed on

the basis of impending incidents (near- misses) and not only on the

basis of actual incidents. And clearly that is a tough job, since these

signals are weak and difficult to discriminate between the information

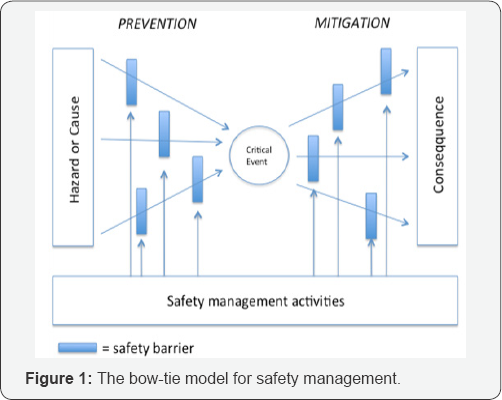

overload that the organisation is suffering from on a daily basis (Figure 1).

The thinking in barriers is based on the bow-tie model sometimes also called the Swiss cheese model [5-7].

The model combines the concepts of cause, event and effect. Every event

can have a number of causes and once the event is triggered it can lead

to a variety of effects. The bow-tie model is highly structured and a

nice way to schematically represent the whole process. The emphasis in

the bow-tie model is on the barriers, between cause and event and

between event and effect. Preferably in this approach the intent is to

prevent an event to happen by throwing in a number of barriers to

prevent the cause triggering the event. Those barriers can be physical,

but also behavioural.

In case an initial barrier did not work or was

omitted, the cause might trigger the event and the next set of barriers

is meant to prevent the consequences of the event, the effects, by

throwing in barriers between event and effect. To give a simple example,

think about driving a car. Driver training, traffic rules, speed limits

are all barriers for preventing collisions. The safety belts and air

bags and the like are all barriers to prevent injuries once an event, a

collision, has happened. Modern incident investigation is aimed at

identifying the barriers and whether they have worked or not. With the

benefit of hindsight an incident can then be followed up by improving

the safety systems in case a barrier was missing or retraining staff in

case a barrier was broken deliberately, to prevent the accident from

happening again.

The two key words in the bow-tie model are: barrier

and scenario. The origin of the term barrier is probably associated with

the energy barrier model that can be traced back to Gibson [8]. The term safety barrier can now be found in regulations, standards and scientific literature [9].

The bow-tie model visually combines fault tree analysis on the left

side and event tree analysis on the right side. The critical event sits

in the middle. Between the critical event and the two ends, barriers can

be put in the paths that run from cause to event to affect, the so

called scenario. For a critical event there can be multiple causes,

consequences and scenarios [10].

The scenarios are the paths/arrows going through the critical event.

The bow-tie model emphasises the importance of managing the barriers.

This highlights the fact that accidents can be prevented as long as the

barriers are managed in the proper way, from design, via specification,

construction to operation, maintenance and final abandonment. Another

solution could be to totally change the working method so that the

scenario does not apply anymore.

The most important step towards an improved safety

performance is the change in the behaviour of both staff and management.

Many companies have accepted that and have developed their own ways of

changing behaviour. Programmes to reach the hearts and minds of staff

are examples of this approach. The most important message is that the

bigger the belief that safety is not just a coincidence, an act of luck,

but a dedicated choice that is highly dependent upon the interaction

between staff. Changing the behaviour is not something that can be done

overnight. The company Dupont is a good example that this can be done,

but it has taken something like 20 years to reach the excellent safety

statistics that they have today.

The Dupont Bradley curve [11]

is a good example of the growth process that staff and management have

to go through to meet the objectives: a goal of zero incidents is

possible. In the words of Dupont: “In a mature safety culture, safety is

truly sustainable, with injury rates approaching zero. People feel

empowered to take action as needed to work safely. They support and

challenge each other. Decisions are made at the appropriate level and

people live by these decisions. The organisation, as a whole, realises

significant business benefits in higher quality, greater productivity

and increased profits." The Dupont Bradley curve supports the

understanding of the mind- shift that is required by all involved and

the actions that go with this shift to realise a mature safety culture.

The attitude changes gradually from reactive, via dependent and

independent to interdependent. In the final stage people feel ownership

for safety and take responsibility for themselves and others as they are

firmly convinced that real improvement can only be realised as a group.

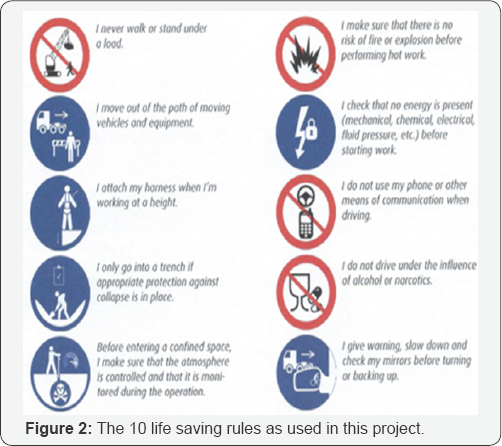

Finally, based on experience and a thorough analysis

of incidents, accidents and fatalities that have happened in the process

industry over the last few decades, has led to a number of so-called

life saving rules. The most important causes of accidents and fatalities

have been translated in this set of rules. You could call it the do's

and don'ts of working safely in the industry. These rules originate from

the oil and gas industry and as a consequence care has to be taken when

applying these rules in a different industry. For instance the main

causes of fatal incidents in the construction sector can be slightly

different than the main causes of fatalities in the process industry. So

other rules will apply. Workers should be able to relate to the rules

and recognise them otherwise it will be counterproductive. In some

instances translating them into a number of different languages is a

necessity when the majority of the workforce consists of workers coming

from abroad (Figure 2).

The project

The project and its participants will be kept

anonymous. Reason for doing that is that the authors would like to tell a

more generic story. Coming up with a detailed story with all the

project specifics might put people off and prevent them from looking

into the real learning. The article aims to enable other project

managers to adopt or adapt the learning to their own project and special

circumstances. Furthermore, by naming companies, contractors,

subcontractors and suppliers, the wrong impression might be given. The

project is not the result of individual behaviour or excellence, but a

result of a joined effort of a number of companies who worked closely

together to reach this result.

The project under study is an infrastructural project

somewhere in the Netherlands. The total capital expenditure was 300

million Euros and the planned duration was 54 months. The works were a

combination of civil works, technical installations, road works

including the commissioning and start-up. The principal was a limited

company with the regional government as their single shareholder with

the director and the project manager as the only two staff members. All

other staff of the principal's project team was direct hires and

freelance professionals hired for and by the project team and 2 staff

seconded by the regional government. The works were tendered as a design

and construct contract and rewarded at the lowest price. The final

construction company selected was a consortium consisting of four

individual companies. The principal stated as one of the tender

requirements that the installation contractor should be an integral part

of equal partner in the consortium and would be participating from day

one. Most often in these types of infrastructural projects, the start-up

of the product is seriously delayed because of the installations. By

having them already onboard from the word "go" this risk was recognised,

controlled and minimised.

The project manager originated from the process

industry where he learned the trade. He had previous experience in

executing similar projects for the regional government. The safety

statistics of the earlier projects made him and the director look for a

better way of managing this project, with less incidents, better

statistics and an overall better project performance. He came to the

conclusion that in order to deliver a better project performance, safety

had to be managed. As a consequence right from the start of the project

safety got priority. Quite often safety is seen as a responsibility for

the contractor, which is indeed an important part of the Dutch labour

laws. But the principal took also a part of the responsibility in this

project. The principal declared the boundary conditions within which the

works will be executed. The project manager and the director challenged

the contractor's right from the start to work safely and stated their

ambition to have no fatalities and a LTIF of less than 5 at the end of

the project. That clearly requires an attitude that assumes that

accidents and incidents are not a part of the job, that they are not

just a reality in civil construction projects. They made safety a

deliberate choice. The stronger the conviction that safety is not just a

coincidence but the result of interaction between staff, the less

accidents will happen. So the intent was to shift to the right on the

Dupont Bradley curve to a more interdependent behaviour towards safety.

It was the firm belief of both the director and the

project manager that by getting the safety behaviour right the project

would also perform much better. That has been the guiding principle for

the project management. By thinking in risks that could jeopardise the

execution you are dealing with safety, but as a next step you also

translate these risks into the planning and in that way you also control

quality, costs and time. So safety first has more than one meaning for

this project.

The practical side of changing behaviour

After selecting the successful bidder, on the lowest

price, principal and project manager made an incentive available for

improved safety performance of the project. This was deliberately done

after the award so that the various contractors would not price in that

incentive in their bids. So in this situation the price of the contract

was clear and an additional incentive was put on the table for improved

safety. The second step that was taken that is essential for the success

of the project is that the principal, the project manager, the project

team of the principal and the project team of the consortium were all

housed in one barrack at the construction site. They were sitting next

to each other under one roof and sharing the social areas, canteen and

the entire infrastructure required for a seamless execution. They were

literally acting as one team [12]. In a recent study on collaborative relationships between owner and contractor in capital project delivery [13],

it was concluded that these owner-contractor relationships should be

based on affective trust, shared vision, open and honest communication

and senior leadership involvement. One could argue that these are indeed

the essential elements in the successful cooperation in this project as

well.

Safety performance can be influenced at a number of levels and in all phases of the project:

a. Design: In the design phase attention should

already be given to safe operations after completion and safe execution

during the construction phase;

b. Technical: The materials and the tools that are used during the construction have to be safe and fit for purpose;

c. Organisation: Procedures have to be in order, correct, clear and workable and have to be complied with;

d. Behaviour: Staff has to work safely with all the tools and procedures at their disposal.

The technical and organisational steps can be

realised quite simply. The most important safety rules, the ten life

saving rules were made clear to all staff (and visitors), when entering

the construction site, and they are spread around the construction site

and the office building as a constant reminder. Furthermore, there is a

detailed system of work instructions for the construction site. They

start with instructions at the entrance gate and are extended to

detailed work instruction and risk inventarisation.

Also a Last Minute Risk Assessment, to be done just

prior to starting the work, is an essential part of the safety culture

on site. Close attention is also paid that the correct and safe

materials and tools are being used. When the materials or tools are not

in order the work will be stopped and only continued once the right

materials and tools are available. This is typically a role for the

contractors because these are already prescribed in the labour

legislation. Unfortunately not every site adheres as strict to these

rules as should be done. On this project everything is checked and

stopped when necessary.

Strict compliance is adhered to. However, influencing

the behaviour is the most challenging part of the safety journey. When

you are able to influence the behaviour, you will make a difference.

Looking back at the situation in Dupont it took them 80 years to go from

a LTIF of 80 in the 1920's to a LTIF of 0.2 in 2000. So much time is

normally not available in a project. So different measures have to be

taken. Rewarding the right type of behaviour and punishing the wrong

behaviour can accelerate behavioural change. This project has chosen the

positive approach. An incentive system has been set-up after the

finalisation of the contract. The incentive system knows a few reward

levels: the consortium level, the individual workers/ teams and the

staff in general.

A word of warning is justified at this place. It is a

good thing to make sure that everybody is working towards the same

goal. That all noses are pointing in the right direction. But you have

to be absolutely sure that that holds for everybody. Principals have a

tendency to crank up the pressure in order to be ready on time. This

will always go at the expense of the safety when the contractors are

still too much reactive, situated on the left side of the Bradley curve.

Short cuts are taken, precautions forgotten and accidents are waiting

to happen.

The consortium could earn a safety bonus every month

that could total up to one million over the course of the project. The

monthly percentage was established on the basis of safety plans and

inspections and observations on the construction site. Those inspections

were again executed together. Small and large issues were addressed and

reported. Small because many small issues can lead to a disaster

conform the Heinrich triangle. By controlling the small, it was believed

that the big issues could be prevented. Three types of issues were

recognised, so called A, B and C observations. A C is a small

imperfection, a B is something unsafe but not immediately dangerous, but

to be corrected before it could grow out of control. An A is an

imminent danger. Work will have to be stopped and corrective actions

taken.

The scores observed during the inspection were the

basis for calculating the bonus. The procedure also contained a form of

punishment. A lost time injury would cost the consortium 50.000 Euro and

a fatality half a million. That would mean that even in the worst case

of a fatality the consortium could still earn the bonus if the rest of

the work was done well and safe. For the external experts that we

consulted for their opinion on the overall approach of managing this

project, this was actually a sore point. With this penalty system it

looks like the principal is putting a price on a human life, which could

never be the intent. Furthermore, they found that it is remarkable that

the principal is rewarding something that is a legal requirement

anyhow.

In order to make sure that not only the consortium

would benefit from a safe execution on a monthly basis an excelling

worker or an excelling team in the field of safety would be put in the

limelight in the monthly safety meetings. They would receive a "safety

certificate" and a money award. The certificate would be granted after

close consultation between the principal, his project team and the

consortium and officially handed over in the presence of all staff. This

became something to strive for. Every team, every worker, every company

wanted to receive this reward. In this way safety and safety

performance became a living subject for all workers. People were proud

to receive a certificate, and actually the management of the

subcontractors came to the meetings to receive the awards for the

company. It clearly attracted attention.

But safety awards alone were not enough to change the

culture. The consortium issued strict rules and procedures for the

management of safety. Subcontractors with more than 20 staff on-site had

to have a safety advisor. The supervisors on the construction site had

to be able to communicate in Dutch, English or German and to instruct

their staff in their own language. In this way it was made sure that

language would not pose a barrier to improved safety performance.

Finally, all workers received a present when the

monthly safety score would be above 75%. These statistics were made

visible in the canteen and people kept a close track on the performance

in this way. A simple safety thermometer was developed consisting of a

number of transparent tubes for each month and balls representing the

inspections. Above 75% the balls would turn green, between 50 and 75%

the balls were blue and under 50% the balls would turn red. The presents

were simple, for example a safety hammer or are freshment. By handing

out the presents there was again a moment to focus on safety. Every

opportunity to focus on safety has been taken. All workers of the

principal had full basic safety certification. Meetings, periodicals and

a website were utilised to spread the message. No escape possible. Also

externally the message was communicated, not only to inform other

projects about this approach but also because the internal acceptation

becomes bigger once stimulating external reactions are received. Not

only have presentations been given to other projects, they have also

been invited to visit the construction site and experience the approach

via direct contact with the workers.

The approach taken by the principal and his project

team has definitely paid off. The project was delivered with a safety

statistic that was one order of magnitude better than the reported

statistics in the building construction sector. The LTIF for the project

was 3.1. But that was not the only accomplishment: the project was

delivered 6 weeks ahead of schedule and the budget was under spending by

25 million Euros or 8%. A truly remarkable result. Not yet a zero

incident result but certainly showing that also projects in the civil

infrastructural industry can be delivered safely, as long as the intent

and the belief that such a result is feasible is there and communicated,

advocated and shown throughout the whole project.

Evaluation and Analysis

In the final stages of the execution of the project

the authors have had the opportunity to interview a number of involved

staff of bothproject teams, the construction manager, the principal and

the management teams of the parties making up the consortium. Across the

board the experiences are positive. There is of course pride in the

result obtained. Some of the remarks of the members of the management

teams clearly indicate to us that they still have a long journey ahead

of them. Their behaviour is still highly reactive and clearly positioned

on the left side of the Dupont Bradley curve.

A lot of the credit is given to the project team of

the principal. According to all management teams they made it happen and

all management team members are uncertain whether the same results can

be realised with a different principal. They openly advocate now that

they see the benefits but they are not certain yet that they can pull it

off on their own. ]

The principal and his project manager have clearly

taken the initiative in this project. The fact that they were so

convinced that an incident free project is feasible has made a world of

difference. They have shared their ambition, showed their beliefs and

conviction and in this way pulled along with them all the individual

management teams. This clearly resonates in the interviews and

discussions with the managers of the consortium and their parent

companies. The interviewees admit wholeheartedly that making the

incentive available after awarding and signing the contract was a wise

decision. In any other situation the price of the incentive would have

been absorbed in the bid and would not have had the same power as it now

had. They have shown together that safe operations in the civil

construction industry are feasible and they do believe that the

incentive is not a necessity to make this happen but it definitely eased

the process.

They all support the fact that the increased

attention for safety has elevated the whole execution of the project to a

different, higher level. It is not only the safety statistics that show

an improvement, the whole management and execution of the project has

improved, with visible and positive results. A proper work preparation

is seen as a necessary condition that results in a more stable and

prepared work place and thus a safer workplace.

They have seen now what is possible and it is up to

them to continue this behaviour on the next project of their company

together with the same companies or in different constellations as

theyappear in projects. They owe it to their staff and shareholders to

continue the approach. The building sector is different from and

possibly more dynamic than the process industry. But that offers

opportunities for innovation and improvement. Unfortunately these

innovations are hardly ever taken in the field of safety. When the

companies are not able to learn from this approach and hold on to it,

then they will never shift to the right side of the Bradley curve. And

that is they should be. That is what staff should be demanding.

Conclusion

The learning of the project understudy is loud and

clear. What will happen with this experience in the near future is very

uncertain. The management teams of the consortium partners, the

contractors that have to carry the torch, are somewhat ambiguous in

their approach: they say the right things, but their actions should show

their change in behaviour. As long as in the building industry in the

Netherlands fatalities are still accepted as a given, then there is

still a long road ahead. Contractors' main purpose in life seems to be

making money, logically. But not only the contractors are to blame, not

all principals clearly steer the contractors on the basis of their legal

responsibilities to organise the works in such a way that it is

executed safely Instead the principal is paying a bonus to work safely.

That is the world upside down, but as long as the contractors are as

reactive as they are, this probably will work. From our other studies

and observations we are convinced that as long as the principal steers

on the legal requirements (safety behaviour), quality, costs, planning

and work preparation the works will be executed more efficiently (less

rework that was already budgeted for) and the final performance will be

that the quality of the work delivered and the accompanying safety

performance will be better. In short, the contractor will have worked

more efficiently and saved money as a consequence (profit). In our view,

safe working is efficient working and will lead to additional profit.

The approach as described in this case study is very much in line with results of earlier studies [14]

into improving labour safety. In that study 17 improvement trajectories

have been evaluated. The most important lesson from that study has been

that it is not only about reward and punishment, but it is about

holding the dialogue: a lively dialogue about safety in all layers and

between all layers of the organisations that are working together. The

ultimate aim of these dialogues or interventions is that all involved

are learning from it, that is the central theme. A few of the tips from

this study have clearly been practised in the present project. The

involvement of senior management is essential, rewarding good behaviour,

learning from each other and advertising results are some of the

practices.

The present project team has handled a number of

things very well. However, it should be realised that every project

might need a different approach. Solutions fitting the situation will

have to be used and the tools developed for the specific industry should

be used. One should also realise that small companies are not just

small “big companies” and small projects are different from large

projects. Building a road is different from building a house, and

painting works are clearly different from installation works. The

organisation is different so the work circumstances have to be arranged

differently. As a consequence, a transfer of practice from one industry

to the next will not automatically work. One size does not fit all and

the approach has to be fit for the purpose and fitting the industrial

environment.

The main learning that can be and should be

transferred to other projects are: 1) an integrated front-end

development with all the main players present from the start (the

installation contractor as equal partner in the consortium); 2) all the

parties acting as one team throughout the whole project and 3) senior

management commitment from all parent organisations for the approach

chosen. These learning are generally applicable and should be practised

more by other projects, big or small, to guarantee a better project

performance in the future.

Acknowledgement

This research did not receive any specific grant from

funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors would like to thank the project team and the management

board for their cooperation in and openness during the interviews.

Without their support this article would not have been feasible.

For more open access journals please visit: Juniper publishers

For more articles please click on: Civil Engineering Research Journal

Comments

Post a Comment